Kaunas, August 7

I am stuck in

Kaunas, Lithuania's second city, for couple of enforced days off. Two days ago, as soon as I arrived here and set up my tent, my long-suffering freewheel, the bit inside my rear wheel hub that lets you coast without pedalling but then start accelerating when you start pedalling, died. It was actually kind of funny; one moment I was pedalling along, and the next my legs, pedals, chain and back gears were all spinning madly, but I was slowing to a stop. Within a few seconds, my bicycle was now an expensive and uncomfortable scooter. I scooted back to the campsite, and the next morning walked into town with my rear wheel and a spare hub that I had bought in Slovakia when I first realized that the strange noises I was hearing were presaging the demise of the freewheel. I was lucky that this happened in a biggish city in a cycling-mad country, rather than (say) in the middle of the forest in Belarus. I found a bike store that is apparently, as I type, rebuilding my old wheel (rim, gears, spokes, brake rotor) around the new hub. I hope it all goes to plan, and that at 10 am tomorrow I will be ready to ride out of here, fattened up on beer and Lithuania's great contribution to the world of beer snacks, deep-fried rye bread. Having lost two days of riding, I will have to modify the end of my route and skip the west coast of Lithuania in favour of a straight cross-country shot north to Riga.

I was actually, in a way, pleased that the freewheel broke, although I hate the loss of cycling time. This more or less completes my career grand slam of breaking things that can be broken on a bicycle. Here's a more-or-less complete list of different broken bits over the past 21 years of cycle touring.

- Spokes (beyond counting; once broke 24 on one trip)

- Flat tires (ditto)

- Shredded outer tires (once went through 14 in a single year of touring, before getting Schwalbe Marathons)

- Handlebars (hilarious slow-motion break as I sat waiting at a traffic light)

- Pedal (had to take a taxi out of Nagorno-Karabakh just to find a new pedal)

- Front chain rings (gears)--most recently in Przemysl, Poland

- Chain (worn many out, but broken them too)

- Derailleur (destroyed one in Bulgaria that required a couple of bus rides to find a new one)

- Bottom bracket (several)

- Frame (cracked and rewelded previous frame in Kyrgyzstan)

- Braze-ons (the little rings that allow you to screw racks onto some frames)--broken and rewelded in several Caucasus towns

- Wheel rims: on this trip and at the end of my Balkan Blitz too. I need to have a bomb-proof 48-spoke tandem rear wheel built, I think

- Headset bearings

- Pedal cranks (had to have them hacksawed off recently in Switzerland)

- Saddle (ever tried riding 70 km with no seat? Luckily it was all downhill)

- Rack

- Rack screws

- Front forks (OK, bent but not actually shattered--yet)

- Seat post (again, bent rather than shattered, but once you bend it it's pretty much useless)

Anyway, this allows me the chance to bring the blog up to date. My last update was pretty selective, dealing as it did with sites associated with the Holocaust. Here I'll try to fill in the gaps between Lvov and here.

I was stuck in Lvov for an extra day because of bike repairs. I eventually managed to get my rear gear cassette loose with the help of a bike mechanic from the Torpedo bazaar on the outskirts of Lvov. It took 20 minutes, two strong adult males, a metre of chain to immobilize the gear cassette, a huge wrench with a steel pipe for extra torque and the mechanic jumping up into the air for more leverage to get the old cassette loose. I rather think Dom Cycles overtightened it before the trip! I sat out the inevitable afternoon thunderstorm talking to Taras, the mechanic. It was a typical post-Soviet conversation, about how the Ukraine is going to hell in a handbasket, ruined by corruption and inept government. He was so down on the future that when I remarked on how much rain had been falling on me along my route, Taras replied "Even the weather is getting worse.

It was much better in Soviet times! Now it's either too hot or too rainy in the summers!" That's a man deeply mired in post-Soviet depression!

After that, I went to cheer myself up in Lvov's wonderful city cemetery, full of 19th-century Polish graves ornamented by deeply-aged stone angles. Joanne was always a fan of cemeteries and photographing them, a taste that I acquired from her over the years. After this, and more yummy cake and hot chocolate at another of Lvov's wonderful cafes, I was ready to hit the road the next morning.

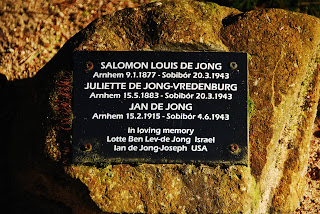

My ride through eastern Poland was covered in the previous post, as I rode through Belzec and Sobibor. I just wanted to add that

Zamosc, a town I had not originally intended to visit, was an unexpected architectural highlight.

It was laid out as a perfect Renaissance planned town in the late 1500s, and still looks like a piece of Italy transplanted into mostly Baroque Poland. The main square, with its near-perfect symmetry and soaring Town Hall, is rightly UNESCO-listed and is a perfect spot to eat, have a beer and people-watch. I actually camped for once that night, as the monsoon rains stopped for two days. At dinner, I spent nearly an hour trying to decide whether another restaurant patron was my friend Greg Swanson. He looked physically identical, with many of the same mannerisms, but from what I could tell he was speaking Polish to his companion, and looked just a little too broad in the shoulders. If it wasn't Greg, it was a perfect doppelganger.

The next day's ride, through Sobibor and on to Okuninka, was also rain-free, the first two-day interval without rain since Romania, although there was rain off in the distance, making for a great rainbow. The Carpathians were well and truly behind me, and the riding was almost Dutch in its monotonous flatness by the end of the day. As much as it's sometimes nice to trundle across the flats at a good clip, I find that for cycle touring a lack of hills makes my mind wander and I end up missing most of the scenery.

I entered country 102, Belarus, the next day, July 29th, at a small border crossing north of Wlodawa. I wanted to avoid the main crossing at Terespol, near Brest, to get through lineups faster. Instead I found myself, for the third time this summer, at a "vehicles-only" border crossing, where I had to load myself and my bike into a passing van in order to get through formalities. I don't understand this; this always happens when leaving the EU into post-Soviet countries, rather than the other way around, and it makes no sense to me. The explanation here was that the computer system needs vehicle registration numbers in order to process border crossings. This sounds completely silly, but I'm sure that somewhere there's a kernel of sense hiding. Apparently just before I arrived, two more cyclists on Dutch passports had just gone across after two and a half hours of arguing and complaining; when I showed up, there was much rolling of eyes and remarks about "tell the Dutch that they can't cycle across this border!" When I finally got into Belarus, I changed some money (at 7200 rubles to the euro, and prices given to the nearest 10 rubles, you end up with an enormous number of small, useless bills!) and then rode towards Brest. The road was pristine and more or less empty; there was a strange post-apocalyptic feeling that reminded me of riding into Tiraspol a month before. I passed through dense forests and small, swampy lakes, seeing only fishermen and the odd car, before finally entering the endless suburbs of Brest.

Brest has a strange road system that meanders all over hell's half acre before finally getting serious about going downtown. I asked some locals for directions (it was good to be able to talk to local people again after a couple of days of muteness in Poland!) and ended up entering town through Brest fortress, one of the most famous WWII sites in all of the former USSR. It was there that the Red Army, who had been occupying Brest for two years,

held out for nearly a month against a huge German assault in June and July of 1941, finally being overrun when they ran out of water in their underground hideouts.

There are dozens of Soviet-era memorials scattered around, with martial music being blared through loudpspeakers, Red Army tanks for kids to play on, huge sculptures and lists of the dead. It really is as though the USSR were still a going concern; even in Russia, I didn't see such an amount of active reverence for the Red Army. All the innumerable war memorials I saw in the country had neatly-tended lawns and fresh floral wreaths; this is perhaps not surprising given that Belarus lost over a third of its population during the war, in mass killings, starvation, partisan warfare, Nazi retribution and Soviet score-settling in 1944. As I left the fort and rode into the downtown core, huge signs commemorated individual war heroes.

The delightfully named Hotel Bug (that's the name of the river that forms the Polish-Belarussian border, and is pronounced Bukh) put me up for the night, and I had a good wander around the streets, trying to get a feel for the city. Several things leap to the eye in Belarus, compared to most other post-Soviet republics, although very similar to what I saw in Transdniestria.

The streets are almost spotless, swept daily by a small army of street cleaners, but also thanks to people using trash cans. There is almost no advertising, probably because there is little private commercial activity. People look, on the whole, quite prosperous; there are no beggars or people picking through the garbage cans, as you see everywhere in Georgia and the Ukraine. Buildings look well-maintained, with fresh coats of paint. Shops have full shelves, but most goods are made in Belarus, with quite low prices, probably partly due to the recent

currency collapse. (Strangely for the FT, they're missing three zeroes on the figures in that article; the ruble went from 3000 to 5000 to the dollar.) Any imported goods are quite expensive in comparison. The streets were full of people enjoying themselves, without the edge of public drunkenness that you always seem to get in post-Soviet countries. One man I spoke to said "Everyone talks about Lukashenko, and he's an idiot, but life here is normal, you know, pretty good."

The next day I rode out of Brest, through industrial suburbs that were full of Soviet-era factories that seemed all to be still working, a radical change from, say, the Caucasus republics and their vast blighted areas of rusting, decaying derelict factories. I rolled through farming towns, realizing that villages are still run on the Soviet kolkhoz (collective farm) basis, with village co-operatives running the local industries, whatever they are (bakeries, breweries, distilleries, sawmills). All the towns looked ridiculously neat, and in the fields combine harvesters were busy bringing in the summer harvest, often followed by storks who were gobbling up the frogs in the newly-tilled fields. It was all a bit like a documentary from the Brezhnev era of the Soviet Dream.

My destination for the day was a UNESCO-listed national park, the

Belavezhkaya Pushchka, famous for hosting the last surviving (semi-) wild herds of European bison. By the time I got close to Kamanyuki at the park entrance, dark clouds had built up and an immense downpour started. When it finally cleared, I went for a look around the museum and wildlife enclosures before having a short ride around the park. It was once an imperial hunting reserve, where Russian tsars came to slaughter big game, and this was why the forests are particularly well preserved, with stands of centuries-old oak trees. The bison were actually introduced here after the last herds were wiped out elsewhere in Europe, and in fact many of the species here, like the red deer, are not native to the area. The bison get supplementary feed in the winter, so they're not exactly 100% wild anymore. I rode around with my eyes glued to the underbrush (good thing there's no traffic and the roads are perfectly paved!), but all I saw was a family of cute little baby wild boar scuttling away under the oaks, and more mosquitoes than I've seen for a long, long time.

That night, with more rain threatening, I slept at the Kamanyuki Hotel Number Two (spot the government-enterprise name!), where 8 euros bought me a luxurious room with satellite TV and a vast bed. Given how infrequently Belarus features on most cycle tourists' minds, there were no fewer than 7 cycle tourists in residence: the two Dutch guys who had preceded me over the border, two Belarussians, and two Ukrainians. It's actually a great country for cycling, with very good roads, cheap food and digs, and little traffic. I rolled out of town the next morning through the woods, where I again failed to see any bison, headed up towards the Polish border before turning southeast towards the park border and the main road from Brest to Slonim. There was no traffic at all, and it was wonderful riding through the forest in complete silence. I eventually exited the park and, somewhere over the next ten kilometres, managed to get on the wrong road, probably in a stretch of road construction. I raced along newly-laid tarmac, loving the forested surroundings, and it was only when my odometer told me that I should have reached Pruzhany and I was still in the forest that I realized something was wrong. I finally found someone to ask, and found out that I was on a new forestry road that doesn't appear on my map. I was 30 km south of Pruzhany, and it was a long, hungry slog to get there for a very late lunch. I called it quits at Ruzhany, where a search for a hotel (I had cycled through a Biblical deluge in the forest, and more rain was on its way) led to a grocery store with rooms above. This time 5 euros was the price, and I slept soundly.

Ruzhany was a bit of dead-end town, where Sunday night was spent by the local inhabitants in buying beers in the grocery store and drinking them in the park, but the next day I rode through one model city (Slonim) to stay overnight in another (Lida). Lida in particular seemed almost like the instant add-water-and-stir Chinese cities that have sprung up over the past decade. Every building in the downtown core, other than the old Lithuanian castle, was brand new, with new paint, new signs and perfectly-laid sidewalks. I splurged on an 18-euro room and was rewarded with BBC World on the TV. The sidewalks were alive with merry-makers, but everything seemed orderly and civilized, and I went to sleep pondering what makes society in Belarus function well, although in an ideosyncratic style. One theory another traveller had is that with all the government factories working, there's little unemployment and people have a sense of purpose lacking in places like the Ukraine, Kyrgyzstan and Armenia. I don't know, but something has to explain the smooth functioning of a country that is technically bankrupt (OK, so are Greece, Ireland and Portugal, and the US is on its way, but you know what I mean). Whatever the case, seeing a country without litter, graffiti, advertising, massive unemployment or visible poverty was certainly a welcome change. Keep your eyes on Belarus;

whatever happens politically or economically, they seem determined to steer their own course.

I rolled out of Belarus into Lithuania with remarkably little border nonsense, and was soon rolling through more dense forest north towards Vilnius. There was more traffic, but the excellent road surface continued right until the Vilnius suburbs, where I had the strangest approach into a national capital, along a narrow, potholed street that seemd to be going nowhere until it debouched at the main gate to the old city. Suddenly there were Western tourists absolutely everywhere (I haven't seen so many Germans, Dutch and American tourists all summer), and the streets were lined by beautiful Baroque facades.

I spent two days off the bike in Vilnius, partly because I loved the place, and partly to let my legs recover. I thought that after time off in Lvov, my legs would stay fresh, especially with such flat cycling, but I think my body is finally realizing that I'm in my forties. My thighs felt as though they were full of lead on the last couple of days of riding, and I just wanted to sleep. I did find time, though, to explore the various museums on offer, and to wander the streets in a state of sensory overload. I would actually rate Vilnius very highly as a European city to visit, up there with Prague, Dubrovnik, Venice, Split and Bruges for beauty and architecture.

The Museum of Genocide refers not, as you might expect, to the near-total destruction of the Lithuanian Jewish population from 1941-44. That's at the Holocaust Museum. Instead, this museum chronicles the determined Soviet efforts to stamp out Lithuanian nationalism and independence from 1939 to 1941 and again from 1944 to 1991. Only a week before Germany invaded the USSR, the Soviets deported thousands of Lithuanian intellectuals and potential leaders to the furthest parts of Central Asia and Siberia, and over a hundred thousand more went after the Soviets recaptured Lithuania in 1944. There's more to the history; when Poland was partitioned in 1793, Russia gobbled up its confederate state the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and the Lithuanians resisted Russification with revolts in 1830, 1863 and 1905 before grabbing independence in the chaos following the 1917 Russian Revolution. The Lithuanians never warmed to the idea of being part of Russia or the USSR, and they led efforts to break up the USSR in the 1980s. The museum meticulously chronicles the arrests, torture, deportations and executions that marked Soviet power in the country, and wandering through the underground KGB prison is seriously spooky.

I found myself admiring the plucky Lithuanians, and I'm impressed with what they've managed to make out of their country in the past 21 years. The country feels prosperous, modern, forward-looking and very European. There's a continuing strain of rebellion, as shown in the "constitution" in a particularly bohemian corner of Vilnius, and a love of Frank Zappa (see the memorial above). It feels as though they've successfully turned their back on the USSR in a way that many other countries can only envy. The city of Vilnius has been transformed into a cycle-friendly cultural hub (have you ever seen police patrolling on Segway scooters?), with Baroque architectural gems and a very outdoorsy, outgoing vibe that seems a world away from Taras and his post-Soviet depression in Lvov.

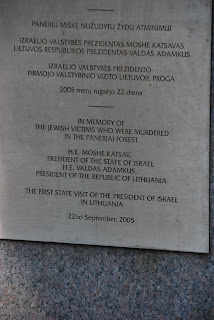

I rode out of town through the Holocaust site of

Paneriai (see previous post) and the fairy-tale castle at

Trakai

(a town inhabited by the truly obscure religious sect known as the

Crimean Karaites; I'd never heard of them; has anyone? Sort of Jewish, but revere Jesus and Mohammed as prophets, only believe in the first five books of the Old Testament) before making my way across hill and through vale to Kaunas. My sideroads eventually turned to sandy tracks and died, so I swept into town on the shoulder of the A1 motorway. Kaunas is like a much smaller version of Vilnius: more Soviet concrete around a smaller historic core, but still a warm, welcoming feel in the old town.

So now it's time to abandon the plan to see the Curonian lagoon and head straight north to Riga and on to journey's end at Tallinn. Six days of riding should see me there with a few days to spare to explore Riga and Tallinn. Let's hope that wheel reconstruction goes to plan!!

Riga, August 12

I have been resting, recuperating and watching rain fall in Riga now for two and a half days, so it's time to pack up for an early departure tomorrow on the last leg of this trip, the 310 km from Riga up to my final destination, Tallinn. I hope that it all goes as easily as my ride from Kaunas to get here!

My friend Sion, whenever weather got cold, windy and unpleasant this winter in the Alps, would refer to it as "absolutely BALTIC out there", and I have to say that so far Latvia has lived up to his epithet, as daily highs reach the low teens, and rain and wind batter the city and the countryside. I hope that Tallinn is more Mediterranean than Baltic!

I set off from Kaunas on August 8th at 12:30, a very late start caused by my having to trudge into town, in driving rain, pushing my one-wheeled bicycle to the bike shop to pick up my newly rebuilt back wheel. I was impressed with the workmanship, and with the price tag: 50 litas, or about 15 euros, for what must have been an hour or two or labour. In Switzerland, it would have been well over 100 euros for the same job.

Riga, August 12

I have been resting, recuperating and watching rain fall in Riga now for two and a half days, so it's time to pack up for an early departure tomorrow on the last leg of this trip, the 310 km from Riga up to my final destination, Tallinn. I hope that it all goes as easily as my ride from Kaunas to get here!

My friend Sion, whenever weather got cold, windy and unpleasant this winter in the Alps, would refer to it as "absolutely BALTIC out there", and I have to say that so far Latvia has lived up to his epithet, as daily highs reach the low teens, and rain and wind batter the city and the countryside. I hope that Tallinn is more Mediterranean than Baltic!

I set off from Kaunas on August 8th at 12:30, a very late start caused by my having to trudge into town, in driving rain, pushing my one-wheeled bicycle to the bike shop to pick up my newly rebuilt back wheel. I was impressed with the workmanship, and with the price tag: 50 litas, or about 15 euros, for what must have been an hour or two or labour. In Switzerland, it would have been well over 100 euros for the same job.

It had stopped raining by the time I got back to the campground, so it was actually a pleasant day for riding. I had changed my itinerary to shorten it because of the lost two days in Kaunas. I headed north and a bit west towards the town of Siauliai and its Hill of Crosses. I passed a few carved devils, one of the great obsessions of Lithuanian popular culture, well documented in Kaunas' Museum of Devils. I didn't make it all the way, but I did manage to cruise 113 very enjoyable kilometres across flat, undemanding terrain, aided by that rarest of creatures, a slight tailwind. As well, I think that the new back hub that I had installed is substantially quicker than the old hub, with less rolling friction. Whatever the reason, I managed to average an unheard-of 22 km/h that day, with long periods of cruising above 25 km/h. It was all easy and enjoyable, and I even managed to camp out in a secluded corner of a farmer's field, my first wild camping in over 3 weeks.

After a wonderful night's sleep, I awoke in the morning to the sound of strong wind rattling my tent. I stuck my head out and was happy to find that it was still a tailwind. I had to cut across the wind for an hour to get into Siauliai, slowing me down substantially, but after that I absolutely flew, often at 30 km/h across the flats, barely pedalling. It was such a wonderful feeling that I barely wanted it to stop.

It had stopped raining by the time I got back to the campground, so it was actually a pleasant day for riding. I had changed my itinerary to shorten it because of the lost two days in Kaunas. I headed north and a bit west towards the town of Siauliai and its Hill of Crosses. I passed a few carved devils, one of the great obsessions of Lithuanian popular culture, well documented in Kaunas' Museum of Devils. I didn't make it all the way, but I did manage to cruise 113 very enjoyable kilometres across flat, undemanding terrain, aided by that rarest of creatures, a slight tailwind. As well, I think that the new back hub that I had installed is substantially quicker than the old hub, with less rolling friction. Whatever the reason, I managed to average an unheard-of 22 km/h that day, with long periods of cruising above 25 km/h. It was all easy and enjoyable, and I even managed to camp out in a secluded corner of a farmer's field, my first wild camping in over 3 weeks.

After a wonderful night's sleep, I awoke in the morning to the sound of strong wind rattling my tent. I stuck my head out and was happy to find that it was still a tailwind. I had to cut across the wind for an hour to get into Siauliai, slowing me down substantially, but after that I absolutely flew, often at 30 km/h across the flats, barely pedalling. It was such a wonderful feeling that I barely wanted it to stop.

I did make myself stop at the Hill of Crosses, however, and it was well worth it. Lithuanians, who must rank with the Maltese and the Polish as the most ardently Catholic nation in Europe, have been planting crosses on this hill for centuries, but the Soviets bulldozed the crosses and spread the hill with manure in order to stamp out the practice. This failed, and since independence, hundreds of thousands of crosses, from the microscopic to the towering, have been erected in a chaotic flowering of popular religion. Most crosses are planted by individuals on pilgrimage, but some carry various messages (Messianic, political, hopes for world peace). The overall impression is of an organic mass of crosses springing from the soil. In the bracing wind, the smaller crosses, often dangling on larger ones, tinkle in the wind like a vast assortment of wind chimes. There were hordes of people there, both curious tourists and Lithuanian pilgrims. I've never seen anything quite like it, and it was well worth the time lost to sailing before the wind.

I did make myself stop at the Hill of Crosses, however, and it was well worth it. Lithuanians, who must rank with the Maltese and the Polish as the most ardently Catholic nation in Europe, have been planting crosses on this hill for centuries, but the Soviets bulldozed the crosses and spread the hill with manure in order to stamp out the practice. This failed, and since independence, hundreds of thousands of crosses, from the microscopic to the towering, have been erected in a chaotic flowering of popular religion. Most crosses are planted by individuals on pilgrimage, but some carry various messages (Messianic, political, hopes for world peace). The overall impression is of an organic mass of crosses springing from the soil. In the bracing wind, the smaller crosses, often dangling on larger ones, tinkle in the wind like a vast assortment of wind chimes. There were hordes of people there, both curious tourists and Lithuanian pilgrims. I've never seen anything quite like it, and it was well worth the time lost to sailing before the wind.

I raced north towards Latvia, stopping to change money at the last town before the border, and then tacked at right angles across the wind to head east towards Rundale Palace. I got there slightly too late to go into the palace and the grounds, but I circled the moat on my bicycle and went as far as the ticket gate, admiring the sheer Versailles-like scale of the place. It was built in the time of Peter the Great by the Italian architect who built the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg, and it absolutely dominates the flat landscape. The gardens weren't on the opulent manicured scale of Versailles, but were still very pretty.

I rode off and found another good field for camping, with a wonderful sunset over golden fields of wheat. I awoke to yet more tailwinds, and this time I had a straight shot into Riga, with no stretches at all against the wind. I made the 63 km into Riga in 2:37, an average speed of 24 km/h, by far the fastest flat day of ing I have ever had on a bike tour. I was almost tempted to bypass Riga and just keep flying along towards Tallinn; I could easily have done 200 km that day without breaking a sweat.

I raced north towards Latvia, stopping to change money at the last town before the border, and then tacked at right angles across the wind to head east towards Rundale Palace. I got there slightly too late to go into the palace and the grounds, but I circled the moat on my bicycle and went as far as the ticket gate, admiring the sheer Versailles-like scale of the place. It was built in the time of Peter the Great by the Italian architect who built the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg, and it absolutely dominates the flat landscape. The gardens weren't on the opulent manicured scale of Versailles, but were still very pretty.

I rode off and found another good field for camping, with a wonderful sunset over golden fields of wheat. I awoke to yet more tailwinds, and this time I had a straight shot into Riga, with no stretches at all against the wind. I made the 63 km into Riga in 2:37, an average speed of 24 km/h, by far the fastest flat day of ing I have ever had on a bike tour. I was almost tempted to bypass Riga and just keep flying along towards Tallinn; I could easily have done 200 km that day without breaking a sweat.

Riga is a wonderful city, bigger feeling than Vilnius although with a smaller Old Town. It's on a broad river, which always helps a town's prettiness, and the Old Town (which is actually mostly reconstructed after the damage of the Second World War) is surrounded by the real jewel of Riga, the belt of Art Nouveau buildings put up around 1900 by Michael Eisenstein and other architects.

I haven't seen as much of Riga as I thought I would. Partly this is because it has been raining almost continually since I got here, reducing the appeal of walking in the streets. Also, I went out on a pub crawl on my first evening here with other inhabitants of the hostel I'm staying at (Fun Friendly Frank's), and spent much of yesterday's daylight hours asleep. I have taken some pictures of the Art Nouveau buildings, rich in carved detail like dragons, gargoyles and Greek gods.

Riga is a wonderful city, bigger feeling than Vilnius although with a smaller Old Town. It's on a broad river, which always helps a town's prettiness, and the Old Town (which is actually mostly reconstructed after the damage of the Second World War) is surrounded by the real jewel of Riga, the belt of Art Nouveau buildings put up around 1900 by Michael Eisenstein and other architects.

I haven't seen as much of Riga as I thought I would. Partly this is because it has been raining almost continually since I got here, reducing the appeal of walking in the streets. Also, I went out on a pub crawl on my first evening here with other inhabitants of the hostel I'm staying at (Fun Friendly Frank's), and spent much of yesterday's daylight hours asleep. I have taken some pictures of the Art Nouveau buildings, rich in carved detail like dragons, gargoyles and Greek gods.

I went through the Museum of Occupation, which details with chilling precision the losses inflicted on Latvia first by the Soviets, then the Nazis, and then the Soviets. Like Lithuania, Latvia suffered enormously between 1939 and 1953, losing some 550,000 inhabitants to murder, deportation to Siberia, flight to the West or death by overwork in German concentration camps. That's about one-third of the country's population, an almost unimaginable scale of loss comparable to Rwanda or Cambodia. It's a tribute to the Latvians that they survived this series of disasters with an undamaged sense of identity and purpose.

I tried to visit the Jewish Museum today, but after a long plod through puddles and downpours, I got there to find that it's closed on Fridays. I did find a Holocaust memorial to the 70,000 Latvian Jews and 20,000 Jews from other countries who died during the Second World War; only a couple of thousand survived in German labour camps. Again, unimaginable horror and destruction.

I went through the Museum of Occupation, which details with chilling precision the losses inflicted on Latvia first by the Soviets, then the Nazis, and then the Soviets. Like Lithuania, Latvia suffered enormously between 1939 and 1953, losing some 550,000 inhabitants to murder, deportation to Siberia, flight to the West or death by overwork in German concentration camps. That's about one-third of the country's population, an almost unimaginable scale of loss comparable to Rwanda or Cambodia. It's a tribute to the Latvians that they survived this series of disasters with an undamaged sense of identity and purpose.

I tried to visit the Jewish Museum today, but after a long plod through puddles and downpours, I got there to find that it's closed on Fridays. I did find a Holocaust memorial to the 70,000 Latvian Jews and 20,000 Jews from other countries who died during the Second World War; only a couple of thousand survived in German labour camps. Again, unimaginable horror and destruction.

Riga is awash in tourists, as it's a big destination for RyanAir, and after a while the hordes of Germans, Dutch, Italians, Spanish and English gets a bit much, especially the proliferation of bars, restaurants and dubious nightclubs around the Old Town. I find myself wishing for the relatively tourist-free streets of Brest or Zamosc. I think Tallinn will be more of the same, and somehow I feel as though the adventurous part of this summer's travels has already come to an end. Maybe Tallinn, this year's European Capital of Culture, will re-excite my sense of arrival.

Peace and (Epic) Tailwinds!

Graydon

Riga is awash in tourists, as it's a big destination for RyanAir, and after a while the hordes of Germans, Dutch, Italians, Spanish and English gets a bit much, especially the proliferation of bars, restaurants and dubious nightclubs around the Old Town. I find myself wishing for the relatively tourist-free streets of Brest or Zamosc. I think Tallinn will be more of the same, and somehow I feel as though the adventurous part of this summer's travels has already come to an end. Maybe Tallinn, this year's European Capital of Culture, will re-excite my sense of arrival.

Peace and (Epic) Tailwinds!

Graydon